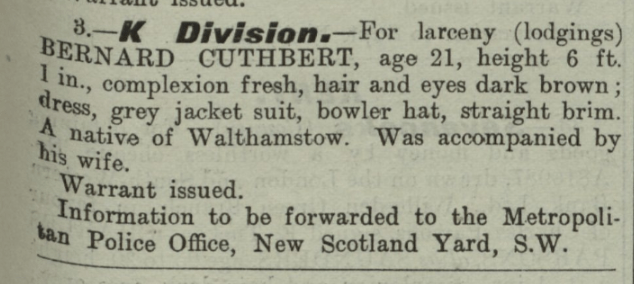

In September 1911, the following appeared under ‘Apprehensions Sought’ in the Police Gazette:

My great-grandfather Bernard Cuthbert was actually just 20 years old at the time. He had never been in trouble with the law before and came from a reputable family – his late grandfather had been the police superintendent of Braintree.

The story is explained in an article that appeared in the Essex Times two weeks later. Bernard had been accused of stealing “a quantity of furniture, valued at £60”, from his former friend and landlord, Harold Wilson Walker. A 50-year-old travelling coal agent, Walker had been born in East London to parents from Derbyshire. He was married with three children, although he and his wife had been living separately for the last ten years.

Walker was called upon first to explain his case. He said he had been on “friendly terms” with Bernard for “some time”. Three years ago, Bernard had introduced him to his fiancée, Kate (known as Kitty), and “after a time”, suggested there were “certain circumstances” that required them to marry, and asked Walker if he could help her obtain employment. The defence asked Walker to elaborate on these “certain circumstances”.

“Well, they were in dire straits; she was out of employment and in lodgings”, Walker said.

The defence pushed for further clarification: “Don’t let any misunderstandings occur. Were the “circumstances” anything to do with the girl’s condition?”.

“There was some suggestion of the sort,” said Walker. “They both admitted it.”

Walker was clearly implying that Kitty was pregnant when she married, however their first child was not born until the following year, eleven months after the marriage took place. It’s possible that Kitty had a miscarriage or wrongly believed herself to be pregnant, but the defence insisted there was “not the slightest truth” in Walker’s suggestion.

The defence asked Walker: “would it surprise you to know that Mrs Cuthbert is not yet 17, and she was not 14 when you were introduced to her?”. Walker replied that he was indeed surprised, and also to find out that Bernard was in fact not yet 20.

In January 1910, when Bernard asked Walker for his help obtaining employment for Kitty, her family were experiencing a difficult time. Her father had been a soldier for many years but in 1906 was finally discharged due to his struggle with alcoholism. The family were forced to return from Scotland, where he had been a sergeant instructor with the militia, to Southend-on-Sea where Kitty’s mother’s family lived. (Bernard, although born in Walthamstow, had moved with his family to Southend a few years previously.) When Kitty’s father left them in 1909, her mother was increasingly reliant on her parents to support her and the children. But in February 1910, Kitty’s maternal grandfather died, aged 73. In desperation, Kitty’s mother went to court to request her absent husband provide financial support to her and their two young sons. Under the Summary Jurisdiction (Married Women) Act of 1895, a wife might obtain a court order if she could prove her husband’s “wilful neglect to provide reasonable maintenance for the wife or her infant children whom he was legally liable to maintain”. The Act specifically referred to infant children; at fourteen, Kitty would have not been considered a financial dependant, and in court was described as earning her own living. While her mother was successful in her claim, the court order was made for the maintenance of only two children – Kitty’s young brothers, aged two and four.

I suspect that her family’s situation is the ‘certain circumstances’ that led Kitty and Bernard to feel that they needed to marry as soon as possible, and reduce the financial burden on her mother. Her young age would have been a factor too – as a fifteen year old girl living in lodgings, away from home, she would have been in a vulnerable position. Bernard would have been keen to marry her as soon as possible so that he could take care of her, but at only twenty himself, working as a paper hanger, he was not in a position to offer her a secure and comfortable home. This was the situation with which Walker offered to assist.

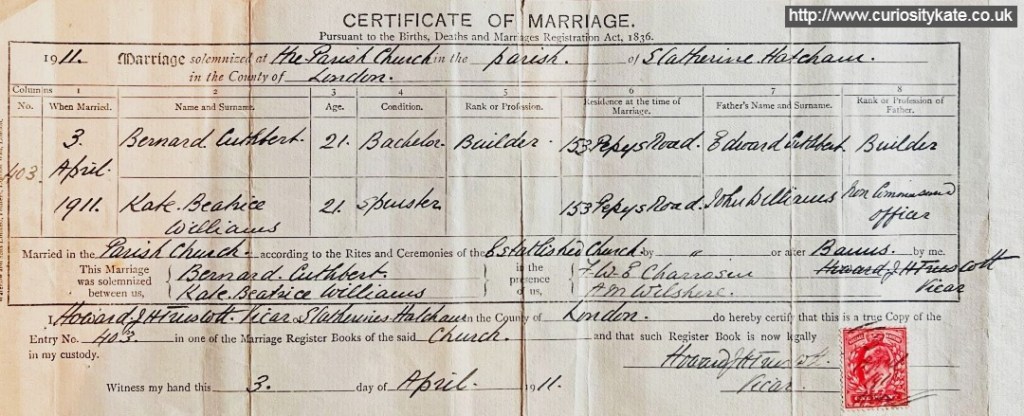

On the 3rd of April, 1911, Bernard and Kitty were married at St Katherine’s, Hatcham. They both gave their ages as 21 (the age at which one could marry without parental consent), although he had only just turned 20 and she was just sixteen. Bernard described himself as a builder like his father, though the court referred to him as simply a paper hanger. Kitty, perhaps out of pride or a sense of loyalty, stated her father’s occupation as ‘non-comissioned officer’ though it had been six years since his discharge and he had more recently been employed as an engine fitter. Bernard and Kitty gave their address as 153 Pepys Road, a boarding house down the road from the church, although neither appear on the 1911 census return which had coincidentally take place the previous night. The witnesses were Annie Margaret Wilshere, a lodger at the boarding house, and Frederick Charrosin, who worked at the post office but was an organist and choir member at the church.

Continuing his statement, Walker explained that “after the ceremony”, they all went to live at the house he owned at 17 Forest Drive, Manor Park. The Cuthberts were to have the “run of the premises and the exclusive use of a bedroom”, at the cost of 10s a week rent. Not only that, but Walker employed Kitty as a housekeeper, paying her 2s 6d a day in return for breakfast and supper. This meant that Bernard and Kitty were effectively living there rent free and receiving 7s and 6d a week as payment for Kitty’s housekeeping duties. It must have seemed an ideal situation for the young couple, who could now live together in security and comfort. Manor Park was technically part of the county of Essex, but was already effectively a suburb of London, popular with aspiring middle class commuters.

Walker claimed that he purchased a ‘quantity of furniture’ for the house, to be used by all three residents. He said after a “dispute”, he returned home on the 13th of September to find Bernard and Kitty missing, along with most of the furniture. The following morning he received a postcard from Bernard, explaining he and Kitty had left with the furniture, and that they were now living at 149 Grange Road, Bermondsey. This was the basis of his claim that Bernard had stolen his furniture.

The defence now presented their case. Mr Stern, the defence lawyer, suggested that Mr Walker was making false accusations to take revenge on the couple, after he had made “overtures” towards Kitty and been rejected. “It was inconceivable that [Bernard Cuthbert] could have any felonious intent to removing the furniture, considering he wrote to the prosecutor the same night telling him where he and the furniture could be found”, he reasoned.

Kitty then took the stand, to explain the truth of their situation. She confirmed that she was sixteen years of age (and would turn seventeen that month), and that she had married Bernard on the 3rd of April, six months previously. She claimed that Walker had suggested that she and Bernard get married, after agreeing to lend them £20 with which to buy furniture. Two months after they moved in with Walker, he asked her if she would go to America with him, and “was very funny” after she refused. “Other scenes took place”, which she either did not describe or the reporter chose not to include, and finally, she told Walker “you have only got me here to ruin my life and when I think how near you have dragged me to the brink of destruction, I hate you”. This is what had led them to finally leave the house, taking their furniture with them. She confirmed that all the furniture they had taken, was now in their home in Bermondsey, and they “had not disposed of a single article”.

The chairman was either completely convinced by Kitty’s evidence, or he had already made up his mind, as “at the conclusion of Mrs Cuthbert’s evidence, the chairman said the bench were satisfied no jury would convict prisoner and he was therefore discharged”.

It was a bold and courageous testimony from a girl not quite seventeen (and, perhaps unbeknownst to anyone but herself and Bernard, four months pregnant) standing up in court to defend her husband and challenge her harasser, at a time when women frequently had no voice. This was history’s first glimpse of the confident figure she would become. Just four years later, she was working at the headquarters of the Australian Imperial Force, in a role that required “considerable tact and diplomacy”. In 1921 she was in court again, this time standing up for Bernard’s sister Nell, accusing her brother-in-law of being a “scoundrel”, who had “treated [his] wife so disgracefully”. In 1939 she ran for the Canvey Island Urban District Council, declaring “I am of the opinion that a woman’s point of view can only be voiced effectively BY a woman” – and won.

As for Bernard, he was never again in trouble with the law, as far as I can tell.