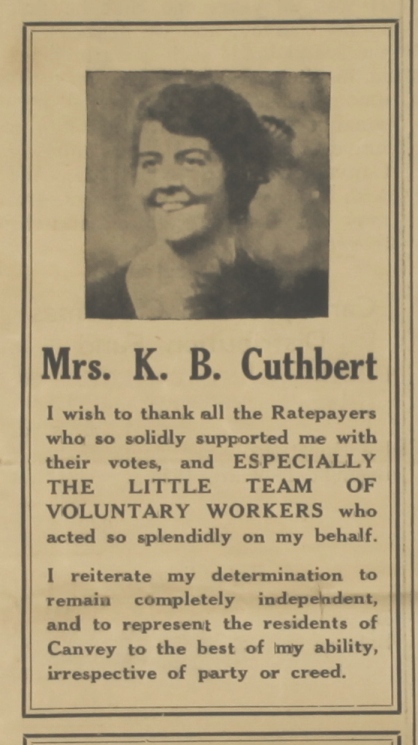

“…[a] remarkable feature of the election is the remarkable success of Mrs K. B. Cuthbert. That it is an achievement we do not think there is any dispute. When she entered the list two weeks ago, she was practically unknown, and it would have been a brave man who would have placed her fourth in the poll. But by Friday evening there were few islanders who did not know her, not only by name but in person.”

Canvey Chronicle, 6th April 1939

44-year-old Kitty, now a proprietor of a newsagents, had been living on Canvey Island for five years when she decided to run for the Urban District Council. “Up to the present I have taken the Englishman’s habit of just ‘grousing’”, she explained on her candidate’s handbill. “I now feel I have the time and health to TRY and do something about it.”

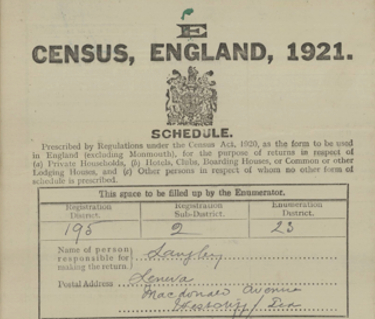

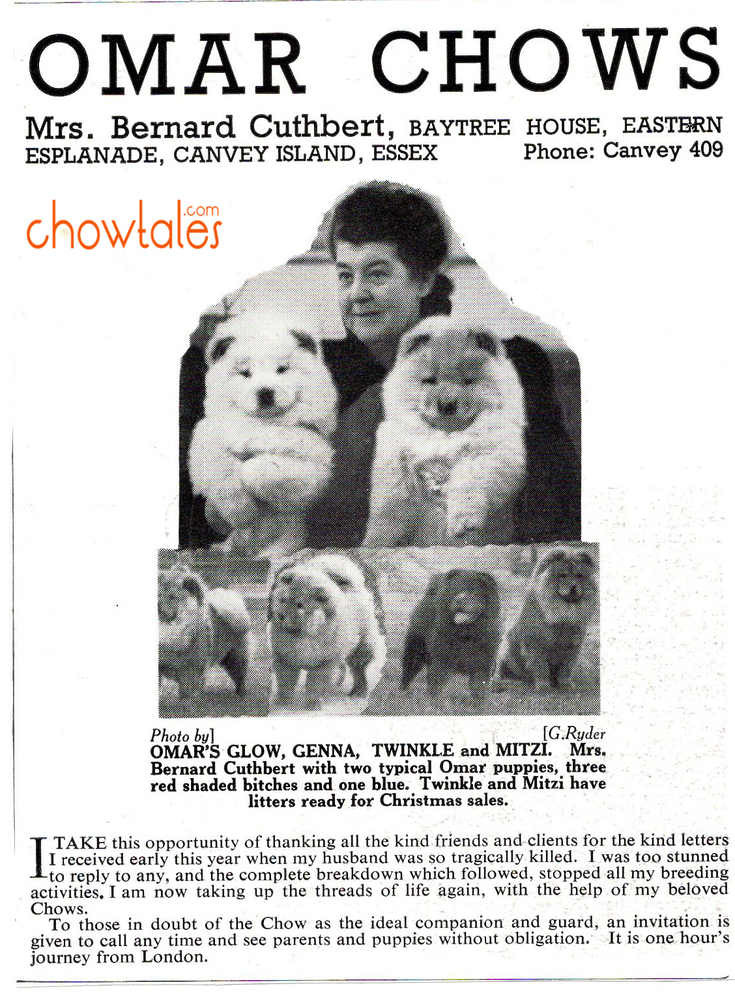

Kitty had moved to the island (from Lewisham) during a period of ill-health and unexpectedly gave birth to her second child just a few months afterwards (her pregnancy had been mistaken for gallbladder disease until the very last moment, resulting in an emergency c-section). Five years later, she was finally feeling in good health and ready for a new project. She stated in her handbill: “Public office is not new to me; During the four years of war I held a very responsible position at the Headquarters of the Australian Forces, and for nine years previous to coming to Canvey I held the position of Organising Secretary, Treasurer and Show Manager of a very large concern in London.” (This ‘large concern’ was the Lewisham & District Canine Society of which she’d been a founding member.)

Now, as the Canvey Chronicle put it, she “threw herself into the business of the election with energy and resource and in the short campaign established a strong position for herself.”

“I am of the opinion that a woman’s point of view can only be voiced effectively BY a woman,” she declared. “If YOU feel I possess the necessary abilities to represent you on your Council, I ask for YOUR VOTE AND SUPPORT. IF I am elected and fail to justify your support, YOU will know what to do when I come for re-election.”

Although a regular attendee of the Labour and Progressive League party meetings, she stood as an Independent candidate, as she felt there was a need for councillors who “are not tied to any interests or ‘clique’ and who will fearlessly express their views of the Island’s interests.” The Island population were soon to discover that Kitty was certainly fearless in expressing her view.

On the night before the election, several meetings were held. Kitty and another candidate, William Money, a 37 year old radio and cycles dealer, held their own meeting at the village hall. The chairman, a Mr Martin, opened the meeting by spreading a union jack upon the table, declaring “we are true Britons”.

After their meeting, Kitty and Mr Martin attended the meeting of the Progressive League at the local primary school. The Canvey Chronicle reported, “The hall was packed for the occasion and the speakers were given a good hearing without undue interruption.” That is, until the meeting was coming to a close, when Kitty rose and asked if she could address the meeting.

The chairman, Mr Mace, refused her request, and the meeting was declared closed. “Nothing daunted, Mrs Cuthbert mounted the platform and began to speak, amidst cheers and jeers”. The Charmain, and Labour councillor Mr Pickett “remonstrated with her”, and Kitty left the platform, only to stand on a chair and begin to speak. Mr Martin loyally waved his Union Jack in support. Amidst the noise as the audience filed out around her, her message went unheard, until somebody suggested they take the meeting outside, and “Mrs Cuthbert left the building followed by a crowd of her supporters.”

Despite not being able to take the platform at the Progressive League meeting, her fearlessness clearly made an impression on the voters, as when the results were announced the next day, she had taken fourth place and was one of the six new members of the Council. (There had been twelve candidates in all.) At the local Labour Party meeting the following week, the Chairman said he believed the “eve-of-the-poll meeting had contributed to her success”.

Kitty was present at this meeting, and thanked the Labour Party for their support, though she was “not a member of that body or any other association”. “Her policy was her own,” the Canvey Chronicles reports, “and she would stand by it whether she lost friends or not.”

She also attended the next meeting of the Progressive League, where she was congratulated by their Chairman, who said “she had put up a sterling fight… her achievement was wonderful.” He failed to mention the Progressive League meeting on the eve of the election at which they had denied her the opportunity to speak.

The Canvey Chronicle summarised Kitty’s response:

Mrs Cuthbert said the great pleasure to her was that she was going into the Council perfectly independently. She had got no governor. She got in by the voice of the people. She “popped out of the blue”, let people weigh her up, and had nobody to push her. She thought they would be good colleagues. If she agreed with what the League wanted she would back them up but she had got to agree.

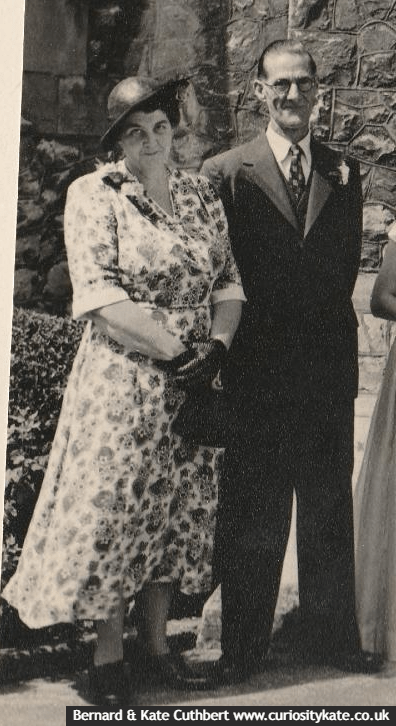

I’m not sure how for long Kitty served as a councillor, but when she died in 1965, her son (my grandfather) Don received a letter from the clerk of the Council expressing their sympathies, acknowledging that she “served this district as a Councillor for many years” before she “retired from public service”. “There are still a great many residents who will remember with appreciation her active interest in local affairs and regard her death as a very sad loss to our community,” the clerk wrote. Interestingly, he also includes that “our present Chairman [Councillor G. A. Pickett] is one of the few Councillors left who was a contemporary of your Mother […] and he is particularly upset by the sad news”. This is the same Councillor Pickett who remonstrated Kitty when she took the platform at the eve-of-the-poll meeting in 1939, but presumably during the time they served together on the Council she was able to gain his respect.

I was lucky enough to find this letter from the Council amongst my grandad’s papers. I went to the Essex Record Office to see if I could discover anything more and was thrilled to find her original candidate’s handbill and a copy of the Canvey Chronicle from 6th April 1939 covering the election. I’ve quoted from both of these sources throughout this blog post. The newspaper also contained the below photo and caption which I ordered as a digital image from the Record Office.

Canvey Chronicle, 6th April 1939.

Reproduced by kind courtesy of the Essex Record Office D/UCi 1/4/2

I don’t know why it took me so long to actually start researching my family history. It’s a topic that always interested me, and every now and then I’d google the names of my great-grandparents, but aside from a couple of photos of my great-grandmother, I never found anything. I knew my grandad had been researching our family history in the 1990s, and I knew his papers would still be around somewhere, but it never really occurred to me to look at them.

I don’t know why it took me so long to actually start researching my family history. It’s a topic that always interested me, and every now and then I’d google the names of my great-grandparents, but aside from a couple of photos of my great-grandmother, I never found anything. I knew my grandad had been researching our family history in the 1990s, and I knew his papers would still be around somewhere, but it never really occurred to me to look at them. Going through all my grandad’s notes and knowing I’m carrying on his research makes the whole process of researching my family history even more personal and rewarding. Back when he was doing this, he didn’t have the internet to help him. He had to visit or write to record offices for information. I have the benefit of online indexed transcriptions from all over the world, which makes things easier in a lot of ways but a little overwhelming in others. Whenever I find more evidence to back up what he already found, or something that confirms a hunch of his, or something that eluded him, I feel so proud, and I know he’d be proud of me. I wish I could talk to him about it all and show him what I’ve found and tackle those stubborn brick walls together.

Going through all my grandad’s notes and knowing I’m carrying on his research makes the whole process of researching my family history even more personal and rewarding. Back when he was doing this, he didn’t have the internet to help him. He had to visit or write to record offices for information. I have the benefit of online indexed transcriptions from all over the world, which makes things easier in a lot of ways but a little overwhelming in others. Whenever I find more evidence to back up what he already found, or something that confirms a hunch of his, or something that eluded him, I feel so proud, and I know he’d be proud of me. I wish I could talk to him about it all and show him what I’ve found and tackle those stubborn brick walls together.